Introduction

Ch.1 – Everything You Need to Know

Summary: Niklas Luhmann created a revolutionary note taking system for him to “think in.” His method allowed him to constantly update and clarify his thoughts and to create a “second brain” over time as a reference. It’s a simple system that scales well.

2) Writing is the process of exploring our thoughts. Writing makes you bring into reality what is in your head.

- Bad note taking doesn’t really have any apparent immediate downside. Your poor note taking system may be sufficient to keep staggering along, but you’re missing out on the extreme upside of effective note taking.

6) You can’t plan for insight. But you can make your workflow conducive to finding new insights. This is the essence of the “Zettelkasten” system.

- Zettelkasten is a German word that translates to “Slip Box.”

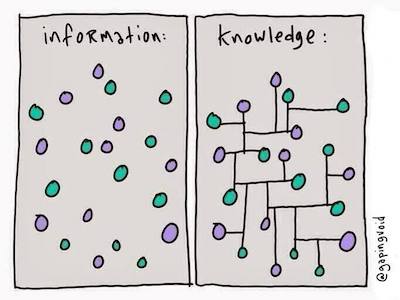

- A Zettelkasten is “a note-taking and organizational method that involves creating an interconnected network of small notes or “slips” of paper (or digital files) that can be categorized and linked together based on their content.”

7) The beginning of a reader’s journey is hard. You discover how limited your knowledge is.

8) The Dunning-Kruger Effect is the observation that intellect/knowledge and confidence are often inversely proportional. The less one knows, the more confident they are about a topic.

- The opposite is Imposter Syndrome, where you are the best equipped for the job, but you doubt your abilities to do it well.

9) The Zettelkasten system (Slip Box) is simple, but that is good. Per Gall’s Law, complex systems grow out of simple systems. Simple systems, once scaled, often become complex. You cannot start with complexity and expect the system to scale.

11) Writing is a nonlinear process. We jump around from sources or even topics when writing. The Zettelkasten system is perfect for writing with flexibility.

12) Niklas Luhmann, a German sociologist and philosopher (1927-1988), invented the Slip Box – a box of systematically interconnected notes. He used this box to document his studies, insights, and thoughts over time. Niklas was interested in a vast range of topics.

13) The Slip Box became Luhmann’s “dialogue partner”. It was like his second brain. He could look through his collected thoughts over time.

14) Luhmann’s project as a University Sociologist was to come up with the theory of society, which was the ultimate undertaking in that field. In 1997 his books were published in a two volume book series title the “Theory of Society.”

15) Luhmann only did what interested him in the moment, what was “easy”. If it wasn’t easy to write about or investigate, he moved onto where his curiosity took him.

- Luhmann published 58 books and 600+ articles in his lifetime.

- Niklas used his curiosity as a guide in his life.

17) You need an external system to “think in” to develop your thinking and capture your ideas over time.

- We make mental jumps in logic when we are simply thinking in our heads. Writing things down reveals our gaps in understanding. Writing forces us to acknowledge and fill those gaps.

- Have you ever tried to explain a concept to someone and couldn’t find the words to express what you wanted to say? You probably did not understand the topic as well as you thought you did.

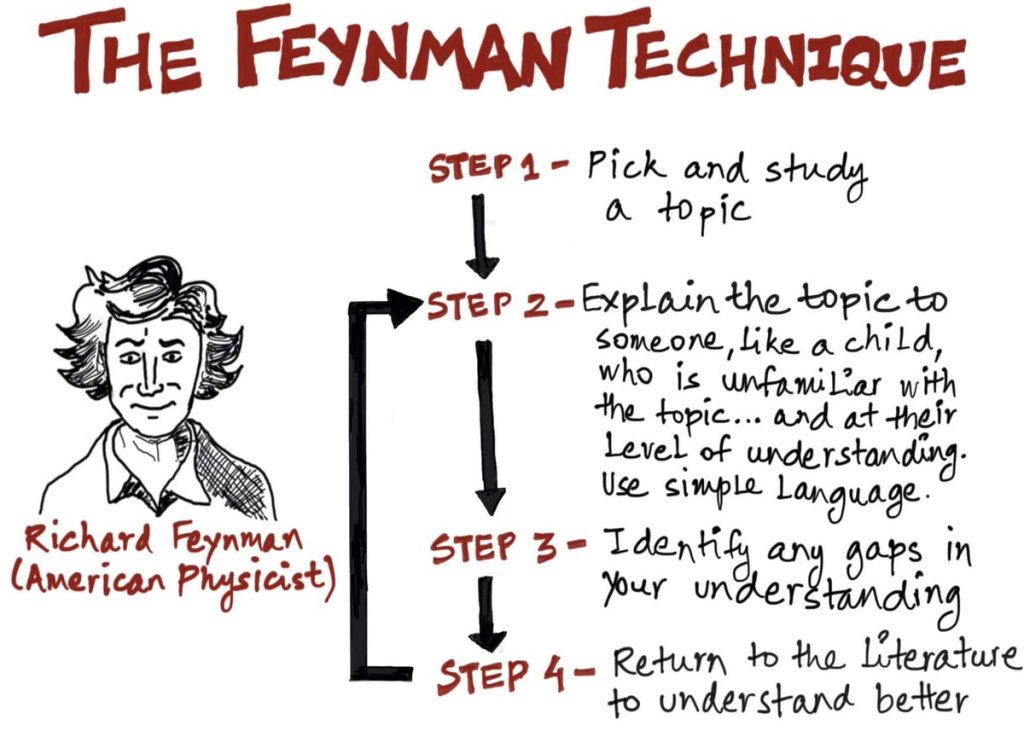

- Related: Richard Feynman used this technique of writing what you (think) you know, in simple language, as a way to test your understanding and improve it.

The Slip Box Manual

(Described as if you were creating a physical Slip Box), see page 18

Disclaimer: I don’t currently use a physical Slip Box, bur rather a digital one (Obsidian).

- You’ll need three locations to store notes:

- One for Bibliographic Notes (to capture notes with official sources [books, articles, etc.])

- A notebook may work well.

- One for Fleeting Notes (to capture random ideas day-to-day)

- Apple Notes, Evernote, etc.

- One for Permanent Notes (a formal note used to capture a single concept)

- Your Slip Box is the storage for permanent notes (or digital software)

- Permanent note cards will go into this box.

- 4” x 6” note cards are a good size to capture one concise thought.

- Use one side for the idea and the other for references

- Permanent Notes should not need any additional context to help your future self understand the idea. They should standalone, complete by themselves.

- Your Slip Box is the storage for permanent notes (or digital software)

- Use notes from research (stored temporarily in your Bibliographic Notes) or daily life (stored temporarily in your Fleeting Notes) as material to create your Permanent Notes. Your Permanent Notes are the heart of your Slip Box.

- When adding a new Permanent Note, connect it to existing notes in your Slip Box.

- Think: ”Within what context should this note be added?”

- Notes should hardly ever be added isolation. Connect them to others notes.

- Linking notes can be done manually by using a simple indexing system of numbers and letters.

- Example: If you have a “Philosophy” section of your Slip Box labeled as “1”, then every note related to the topic of Philosophy could be indexed under that category…

- 1 – Philosophy

- 1a – Stoic Philosophy

- 1a1 – Seneca

- 1a2 – Marcus Aurelius

- 1b – Buddhist Philosophy

- 1a – Stoic Philosophy

- 1 – Philosophy

- You can and should link your notes bi-directionally.

- Your note card on Stoic Philosophy (1a) would reference Seneca (1a1) and your note card on Seneca could reference Stoic Philosophy.

- Bi-directional connections help you map your notes over time.

- Your notes will often be connected to multiple other ideas.

- Example: your notes on Seneca may connect to Stoic Philosophy, and they may connect to notes on mortality or money

- Include sources in your Permanent Notes. It will help you in the future.

- Example: If you have a “Philosophy” section of your Slip Box labeled as “1”, then every note related to the topic of Philosophy could be indexed under that category…

- Maintain your system. Be selective with your Permanent Notes.

- Create an “index” to map out your notes, at least the main categories.

Ch.2 – Everything You Need To Do

Summary: Simplified: a Zettelkasten consists of two main parts: 1) unfinished notes and 2) permanent notes. You can capture “shower thoughts” or notes from books, but then those notes should be processed into permanent notes, which is the core of your Zettelkasten. Permanent notes should be in your own words and should be a complete and concise idea – relevantly inserted and connected into your system.

22) Writing an article, blog, Tweet, etc. becomes easy when you have amassed lots of interconnected notes. When you use a Slip Box, you are pulling from months, years, or decades of your own research and writing. Instead of starting with a blank page, you are just assembling, editing, and expanding on topics you have already explored.

23) You should not simply copy quotes or excerpts into your notes. Put the idea in your own words to grasp it fully. If you don’t, you can fool yourself into thinking you are learning without absorbing the information. Copying lots of direct quotes is a “hoarder’s” version of note taking – high volume, low value.

- Related: “I hear, I know. I see, I remember. I do, I understand.” – Confucius

- You must do more to understand more, and writing is thinking in action.

Writing Papers (Step-by-Step)

23) Fleeting Notes are simply notes to capture things you think of or come across randomly that you do not want to forget. Find a system that works to capture these “shower thoughts.” You don’t want to lose them. These notes should then be processed, discarded or made into permanent notes, within a day or so.

24) Write Literature Notes when reading a book or article. Be selective with what you take notes on, especially with quotes. Make sure to reference the source of your information.

24) You also want to create Permanent Notes, which are refined versions of Fleeting or Literature notes. Only Permanent notesshould be added to your Slip Box.

27) A common day should include reading, note taking, and incorporation of notes into your Zettelkasten. It should be exploratory. Follow your interest.

- “Imagine if you went through life learning only we planned to learn.”

- Capture everything that is profound to you in the moment, even if its off-topic. Then process it later into your permanent notes or discard it.

Ch. 3 – Everything You Need To Have

Summary: Starting is easy. You just need a system to capture quick notes and a system to store and categorize permanent notes. If you want to turn your notes into something more, you may need software to edit and combine your notes; it also may be helpful to have a tool to help with references when required (ex: school papers, books, etc.).

29) Conventional note taking doesn’t scale well. You highlight, take notes, and maybe even write a little about the concept, but you don’t have a simple way to connect it to your body of knowledge and retrieve it years down the road.

31) All you need is:

- Something to capture fleeting notes (sticky notes, notebook, iPhone notes, etc.)

- Your Zettelkasten (CRITICAL): a physical box or software like Obsidian, Notion, etc.

- Ryan Holiday and Robert Green use a physical Slip Box for his note taking.

- Ryan’s explanation here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gT1EExZkzMM

- I use the Obsidian for my Zettelkasten system.

- An editing software edit and finalize content (ex: Microsoft Word)

- A bibliographic reference system (ex: Zotero)

- This is only necessary for published writing like papers or books where you need to have formatted sources.

Ch. 4 – A Few Things to Keep in Mind

Summary: “Tools are only as good as your ability to work with them.” You need to maintain your data and be diligent with up-keep. If you aren’t careful, you’ll end up with a mess.

Four Underlying Principles

Ch. 5 – Writing Is the Only Thing That Matters

Summary: Writing is a clarifying process. You will demand more from yourself and be more engaged if you know you will be writing on a topic. This is especially true if you know that what you are writing will be shared with others; you’ll get helpful feedback through this process.

35) Reading, studying, and note taking are all forms of research.

36) If you cannot recall (access) facts or information, it might as well not exist.

- “An idea kept private is as good as one you never had. And a fact no on can reproduce is no fact at all.”

- In Education, “the professor is not there for the student and the student not for the professor. Both are only there for the truth.” – Alexander von Humbolt

37) You get feedback on your ideas by presenting them publicly (blog, present, debate). If you keep them to yourself, you grow slower compared to sharing your work.

39) If you know you will be writing on a topic, it will keep you more engaged, as you cannot write about something you don’t understand.

Ch. 6 – Simplicity Is Paramount

Summary: The Slip Box method is simple, but the effects of it over time are significant. The process of solidifying your thoughts on an idea, explaining it completely in a single note, and relating it to other notes that you’ve already written helps our overall understanding. It also helps us discover new insights and remind us of insights we may have forgotten.

40) Difference in note taking techniques:

- Old note taking: the question is – “Under which topic do I store this note?”

- New note taking (smart notes) question is: “In which context(s) will I want to stumble upon it again?” You aren’t limited to one category to “store” information.

41) The Slip Box becomes more and more valuable the more it grows. The Compounding Effect of information gathering and connecting is substantial, just like it is for financial investments. Imagine the results 1 year, 5 years, 20 years from now… You will amass a lot of knowledge to draw from.

- The old system of note taking requires that you know what you are looking for and where to find it. The Slip Box makes insights and rediscovering information inevitable as you interact with the system. The Slip Box allows you to discover things you have forgotten. It presents your past insights and connections you’ve made to you again, helping you create new insights.

42) Ahrens talks about a friend of his that collects ideas, quotes, and notes in the old system without much discernment. He never misses a note… He has mountains on unconnected notes, but he doesn’t produce anything with it. He is indiscriminate with his note taking. To him, everything is noteworthy – a “permanent note”. If everything is valuable, then nothing is. You must use your judgment when taking notes. Connecting ideas makes them stick.

44) Permanent notes need to be standalone. They should be understandable on their own merit without additional context to help you understand. As such, your notes are deeply specific and personal, as only you understand what need not be explained versus what needs to be made explicit for you to “get it” when you come across the information again in the future.

- “(Permanent) notes are no longer reminders of thoughts or ideas, but contain the actual thought or idea in written form. This is a crucial difference.”

Ch. 7 – Nobody Starts From Scratch

Summary: The benefit, for current or aspiring writers, is that you don’t have to start from zero. Rather than starting with a blank page or screen, you have you’re Sip Box to draw on for inspiration when looking to write about a topic. You may already have loads of notes that just needs reassembled to produce a blog, article, etc.

49) As time passes and you build up your Slip Box, you will notice clusters of notes that start to build. These are areas that you are knowledgeable and have the ability to potentially write about. You can also look at the interconnection of clusters to see where the interesting insights might exist.

- Questions to reflect on when reviewing your notes:

- What topics are connected in surprising ways? What can I take from this?

- What are reoccurring themes or ideas I’ve been exploring?

50) Ahrens argues that if you structure your Slip Box appropriately and use it, you will eventually have accumulated so many notes (from “research”) that you will have an immense store to draw on for insights and potential writing topics.

- If you do the research and use a Slip Box to take notes, “the problem of finding a topic (to write about) is replaced by the problem of having too many topics to write about.”

Related: “If you’re overthinking, write. If you’re under thinking, read.” – Alex Wieckowski (of @AlexAndBooks_)

- If you have nothing to write about, then you need to do more “research.”

Ch. 8 – Let the Work Carry You Forward

Summary: The process of writing and categorizing new information into our Slip Box is both rewarding and challenging. The association process requires us to confront our old notes. Doing this may reveal conflicting information between the old and new. This conflict forces us to grow and develop our thinking over time to make sense of all our research.

52) Once you get started and are enjoying the process, it will self-propel you.

- The best exercise is the one you enjoy and will repeat. Consistency is more important than intensity.

- Related: “Read what you love until you love to read.” – Naval Ravikant

- It’s better to start with manageable change that you can stick with rather than force yourself into doing something that isn’t sustainable.

53) Making incremental progress is what fuels us. “The most reliable predictor for long-term success is having a growth mindset.”

- Carol Dweck (Stanford Psychologist) has popularized this idea of “growth mindset” through her research and bestselling book Mindset.

- A growth mindset is all about improvement, not perfection. It requires humility and openness to feedback. By accepting feedback, we correct errors in our thinking.

54) “We tend to think we understand what we read – until we try to rewrite it in our own words.”

55) The Slip Box allows you to get your own feedback throughout time.

- If what we write today is in conflict with something we wrote yesterday, we are then challenged to re-examine that inconsistency and adjust our worldview.

- The process forces us to clarify our thinking.

- We update by reflecting on the feedback that our system gives us.

56) It is not solely the Slip Box or our brains that is the key to productive learning and writing. It is the interplay of our brains with the Slip Box that is helpful for discovering new insights and for improving our thinking.

The Six Steps To Successful Writing

Ch. 9 – Separate & Interlocking Tasks

Summary: Master your attention. Avoid multitasking. Separate steps in the creative process (ex: outlining vs. writing vs. editing). Stop planning; start doing. Connect new information to your existing worldview. Create a predictable environment to do your work.

57) Studies show that emails and texts that interrupt our work can reduce productivity by 40%.

· Watching television reduces the attention span in children. Social Media is even worse…

58) Multitasking is bad. Those that are “good” at multitasking feel they are more productive because of it, yet their productivity is actually a lot worse.

59) The Mere Exposure Effect: doing something repeatedly will make us feel competent simply via repetition, regardless of our ability to perform proficiently. We confuse familiarity with skill.

59) The learning process (reading, writing, editing, reflecting, etc.) all take different amounts of focused attention. We need to adjust our focus for each and avoid mixing them.

- Separate your writing from your editing.

61) Your critiquing mind is different from your expressing mind. When you take on the mind of a critic (even for your own writing), you will look at the piece more objectively and find issues with your arguments, organization, etc.

- What we intend on communicating is usually not what we express in writing – especially on our first attempt.

- “We need to get our thoughts on paper first and improve them there, where we can look at them.”

63) “Flexible Focus” is a common attribute of Nobel Peace Prize winners. They have the ability to playfully explore different ideas (they’re curious), and they can also narrowly focus their attention when desired. Nurture your curiosity, but don’t lose your ability to focus. Creativity thrives under these conditions.

64) Becoming an expert requires that we have good examples (lived and otherwise) to draw on. We need to be able to “circle” a problem and “hit it” from different angles. Storytelling is a good skill to develop. We learn more by doing than planning or studying.

65) You learn writing by putting words on paper. Write; make it public. Get feedback. Iterate.

66) “Teachers tend to mistake the ability to follow (their) rules with the ability to make the right choices in real situations.” Theory ≠ Reality

- You can “know” a lot, but not be able to embody your knowledge (i.e. act it out).

· True experts internalize the knowledge and principles such that they don’t need to remember every rule. They act out the internalized principles from which the rules are derived.

69) Our ability to fully understand new information is dependent on the connectedness of that new information via stories, mental models, theories, logic, etc. to what we already know.

- Questions to ask:

- “How does this fact fit into my idea of…?”

- “How can this phenomenon be explained by that theory?”

- “Are these two ideas contradictory or do they complement each other?”

- “Isn’t this argument similar to that one?”

- “Haven’t I heard this before?”

- “What does X mean for Y?”

70) Zeigarnik Effect – open tasks occupy our short-term memory until they are completed OR written down. For some reason, our brain is more likely to forget them if we write them down.

- “The brain doesn’t distinguish between an actual finished task and one that is postponed by taking a note.”

- If you want your mind to mull over a topic, don’t write it down. Your mind will work on it, as it will hold your brain hostage until it is solved or written down.

- If you want to stop worrying about a topic, write it down. Our fears tend lose their edge when expressed – bounded by words.

- Related: Dale Carnegie recommends a similar exercise in his book How To Stop Worrying and Start Living.

- Step 1: Analyze the situation and define the worst-case scenario.Step 2: Resolve to accept that worst-case scenario, if necessary.

- Step 3: After acceptance, seek to improve upon the worst-case scenario.

- Related: Dale Carnegie recommends a similar exercise in his book How To Stop Worrying and Start Living.

By getting the beyond the “what will happen?” stage and accepting the reality of what could happen (worst-case), you can then devote your time and focus on making real progress to improve your situation rather than being crippled by unconstrained worry.

73) “A reliable and standardized working environment is less taxing on our attention, concentration and willpower, or if you like, ego.”

73) Breaks are good for more than just recovery. They are critical for moving information from short-term memory to long-term memory. Taking a walk helps us learn.

- More information (podcasts, books, videos, etc.) is not always better. We need breaks to retain what we’re trying to learn.

Ch. 10 – Read for Understanding

Summary: The goal of studying or reading should be to learn, to understand. Writing and stacking new information onto existing knowledge, although more time-consuming in the short-term, is the most efficient way in research to develop expertise and understanding.

76) Always read with the guiding question at hand: how does this new information affect my currently held beliefs/understanding of other topics?

- Have a conversation with the text you are reading. Don’t accept it blindly – question it.

- Some books can be summarized in a sentence and others are complex.

- Adjust your reading as needed to ensure you understand the material. Don’t compromise retention for speed.

77) Learning for understanding is about getting the essence or the gist of the topic and then incorporating that gist into your existing worldview. You expand your understanding by “hanging” new information onto foundational knowledge you already hold as true.

78) Taking notes by hand has been studied, and they have found that it leads to better understanding compared to typing.

- You have to be selective when writing by hand. Because you must be selective, you must think deliberately to extract the gist of the information such that you can write it down briefly. Its slower and takes more energy.

- You must “separate the wheat from the chaff” to do it efficiently.

- Typing allows you to write more and be less selective with what is important versus what isn’t. It’s faster, so there’s less pressure to be selective.

81) Keep an open mind. Seek disconfirming evidence. Be aware of your own tendency to seek information that confirms your pre-held beliefs. We’re all prone to Confirmation Bias.

83) Rely on your own judgment of what is important and what is not; what is true or false.

- “Nonage [immaturity] is the inability to use one’s own understanding without another’s guidance. This nonage is self-imposed if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one’s own mind without another’s guidance. Dare to know! Have the courage to use your own understanding, is therefore the motto of the Enlightenment.”– Immanuel Kant

- Related: “Let the views of others educate and inform you, but let your decisions be a product of your own conclusions.” – Jim Rohn

85) Writing forces us to confront our lack of understanding. Our gaps in understanding become clear when we write on a topic.

- “If you can’t say it clearly, you don’t understand it yourself.” – John Searle

- Simply reading or re-reading won’t help us learn that well. It will make us think we are learning (via the Mere Exposure Effect), but we aren’t really learning.

- Writing is a true test of our understanding.Read, but then write. Reading by itself tricks our brain in thinking we understand information better than we do.

- “We have to choose between feeling smarter or becoming smarter. And while writing down an idea feels like a detour, extra time spent, not writing it down is the real waste of time, as it renders most of what we read as ineffectual.”

89) Elaboration has been found to be the best way to learn and understand new information.

- Elaboration (also termed “Writing for Learning”) is the process of elaborating on already known topics – expanding and contextualizing your understanding of the world with the new information at hand.

90) Writing and taking smart notes is the process of elaboration that is necessary to actually learn information in a meaningful and lasting way. Thinking of it as “wasting time” is a shortsighted view. If your goal is to actually learn, it will payoff in the long run.

130) Restrict your note such that you capture one idea per note. Keep it brief and use precise language. Your note should not be long to the point where you would need to scroll on your laptop. If you’re using notecards, you are appropriately constrained by the notecard itself.

Ch. 11 – Take Smart Notes

Summary: The process of taking Smart Notes is one of intense selection.

- Of the information we could research, we consume practically nothing.

- Of the research we do, we selectively take Fleeting Notes for ideas that we find striking.

- Of those striking thoughts, we only create Permanent Notes with a small subset.

It’s a process of selecting the important from the trivial. Done right – you’re left with only quality and well thought out notes.

93) Niklas Luhmann’s Slip Box contained over 90,000 notes. On average, he only needed to write 6 notes/day during his career to generate those notes.

- Measure your research productivity by the number of new notes permanent notes you create daily, weekly, etc. Permanent notes are a better proxy for progress in learning than books, articles, or academic papers read.

95) Richard Feynman believed that writing was core to the thinking process. It is not simply the documentation of thought. Writing is the process by which we think.

97) When reading, be selective in note taking. Ask:

- Is this actually profound?

- Is the argument being made convincing?

98) Our inability to remember everything is a feature, not a bug.

- “Selection is the very keel on which our mental ship is built. And in this case of memory its utility is obvious. If we remembered everything, we should on most occasions be as ill off as if we remembered nothing.” – William James

- We forget most things, and that OK – good even. We must forget the superfluous so we can remember the important.

- Story of Solomon Shereshevsky – Shereshevsky was a reporter that never took notes. During a meeting his boss noticed this and found it odd, possibly a signal of laziness, and questioned him on it. Shereshevsky was able to quote back the entire meeting verbatim. He remembered everything. Or rather, he couldn’t forget anything. He could recite facts perfectly, but couldn’t quite understand concepts well (the gist). “The important things got lost under a pile of irrelevant details that involuntarily came to his mind.” Since he remembered everything, he couldn’t separate relevant facts from trivial details – signal from noise.

Ch. 12 – Develop Ideas

Summary: Developing a habit of working with our Slip Box allows us to revisit old ideas and clarify our thinking. We may come across a new piece of data that makes us rethink a pre-held belief. Working with the Slip Box helps update our thinking. The spaced repetition and review of our existing notes improves retention as well.

107) “Ideally, new notes are written with explicit reference to already existing notes.”

108) The value of a Slip Box is subtle, but non-trivial. Trying to organize your own notes without a Slip Box over time is a challenge, because it is all top-down. If a topic changes or grows, you may need to restructure everything. With smart notes, the organization of the notes builds over time and is fluid. You can follow your thinking over time by the notes you have created for them.

- “Notes are only as valuable as the note and reference network that they are embedded in.”

109) Keywords (tags, #) should be chosen carefully and used sparsely. The benefits stem from the interconnection of your notes, not the categorization of notes. Remember – one of the benefits of the Slip Box is that we don’t need to know what we are looking for to find stumble on insight.

- Choosing keywords well – ask: “In what context would I want to stumble on this information again in the future?”

- Choosing keywords poorly – ask: “Which keyword is most appropriate to store this information?”

- We’re not trying to store away information, but rather find it again in the future under in a helpful context.

110) “Indexes“, as Ahrens writes, are seemingly maps of your content, where you have a note that maps out a given topic with all of the linked notes.

- Use these “maps of content” as jumping off points in your Slip Box.

111) “Keywords should be assigned with one eye towards the topics you are working on or interested in, never by looking at the note in isolation.”

115) You will come across the (seemingly) same idea time and time again, but make sure there are not subtle differences. The value in ideas often comes from the differences between them, not their similarities, even when subtle.

- Differences point to where your thinking is flawed or incomplete. It’s a warning that says – “FOCUS HERE! SOMETHING ISN’T ADDING UP.”

- “The constant comparing of notes also serves as an ongoing examination of old notes in new light.” Our thoughts may have evolved on the topic.

- Related: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” ― Heraclitus

118) “You can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang em’ back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form.” – Charlie Munger

119) We co-evolve with our Slip Box. As the Slip Box makes connections, so does our brain. Learning begets learning. Learning becomes fun when we are constantly updating our worldview with better knowledge.

120) “We learn something not only when we connect it to prior knowledge and try to understand its broader implications (elaboration), but also when we try to retrieve it at different times (spacing) in different contexts (variation), ideally with the help of chance (contextual interference) and with a deliberate effort (retrieval).”

- Related: One of the benefits of asking your kids, “what did you learn today?” (besides connecting with them) is that it helps them retain the information. Spaced repetition (reviewing information multiple times spread across time) and active recall (the act of trying to remember something) promotes retention.

126) When analyzing a complex situation, understand that what is absent is often just as important (if not more) than what is present.

- A famous example of this comes from the mathematician Abraham Wald when asked to help the Royal Air Force (RAF), during WWII. Wald was tasked to find the areas of airplanes that were most damaged (with bullet holes) from the planes that returned from battle. The idea was that the RAF would add additional armor to those locations to help protect the planes. Rather than follow instructions as ordered, Wald recommended that they add armor to the spots where they had no records of bullet holes hitting the planes. Why? Because what the RAF forgot was that they had a biased sample to analyze – all they planes they had in their sample had returned from battle; they survived. Survivorship Bias skewed their sample. The relevant information was not the bullet holes, but rather the absence of bullet holes due to their biased sample.

- Video expanding on this topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P9WFpVsRtQg

Ch. 13 – Share Your Insight

Summary: Use your Slip Box to show you what you could write about. Your cumulated notes will point you in the right direction. Your notes will be the starting point of what you write; your task is to use what you’ve already written and reassemble your permanent notes into a coherent argument. Your writing should sharpen your own understanding, which may do the same for others when shared. Follow your interest. Work on what excites you; you’ll do your best work.

132) “I’m never sure what I think until I see what I write.” – Carol Loomis

133) The ability to regurgitate facts has little bearing on one’s understanding of a topic.

136) Given time to develop, your Slip Box will show you what you can write about. Your job is to select and refine these thoughts so you can think more clearly and share your insights with others.

137) People cease to care about learning when they don’t see why the information matters. When new information is not practical or able to be linked to their foundational knowledge, then its not helpful. The why behind the what is critical.

- Related: Simon Sinek’s book Start With Why expands on this.

140) Work on different writing “projects” (school assignments, articles, blogs, etc.) at the same time. If you get hung up on one project, jump to another. Niklas Luhman always worked on what interested him most. As such – “he never forced himself to do anything and only did what came easily to him.”

- Related: Steven Pressfield takes a similar approach. He always starts his next book before he finishes his current one. This does a few things: 1) it helps keep his writing momentum going and 2) reduces the uncertainty that comes with finishing a big project. Asking yourself “what’s next?” can be a daunting question to answer.

142) Overconfidence Bias: our tendency to overestimate our abilities. Another form of this is our tendency to underestimate the duration a task will take. Even people that are aware of and study overconfidence bias can’t avoid it. Parkinson’s Law states that a task will swell in proportion to the time allotted. This seems to be paradoxical when viewed with Overconfidence Bias. Ahrens argues that they can both be true in different contexts. Overconfidence Bias tends to win our in the short term (individual tasks) while Parkinson’s Law holds true in a long-term circumstances (large projects).

- Related: Hofstadter’s Law states that it always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

144) When writing, write a draft and accept that it won’t be any good. It is only a draft. This takes the pressure off.

- When you go to edit your draft, you will be hesitant to remove some text. To permit yourself to cut out unnecessary fluff, you can cut & paste your removals into another document, such that you could return to these “deleted scenes” if you wanted to in the future. This, again, takes the pressure off – this time in the editing process.

Ch. 14 – Make It a Habit

Summary: Make a habit of taking smart notes. Change is hard. Build it into an existing habit if needed. If you aren’t serious about building the habit, then you will likely just do what you have always done in the past.

147) “Watching others reading books and doing nothing other than underlining some sentences or making unsystematic notes that will end up nowhere will soon be a painful sight.”

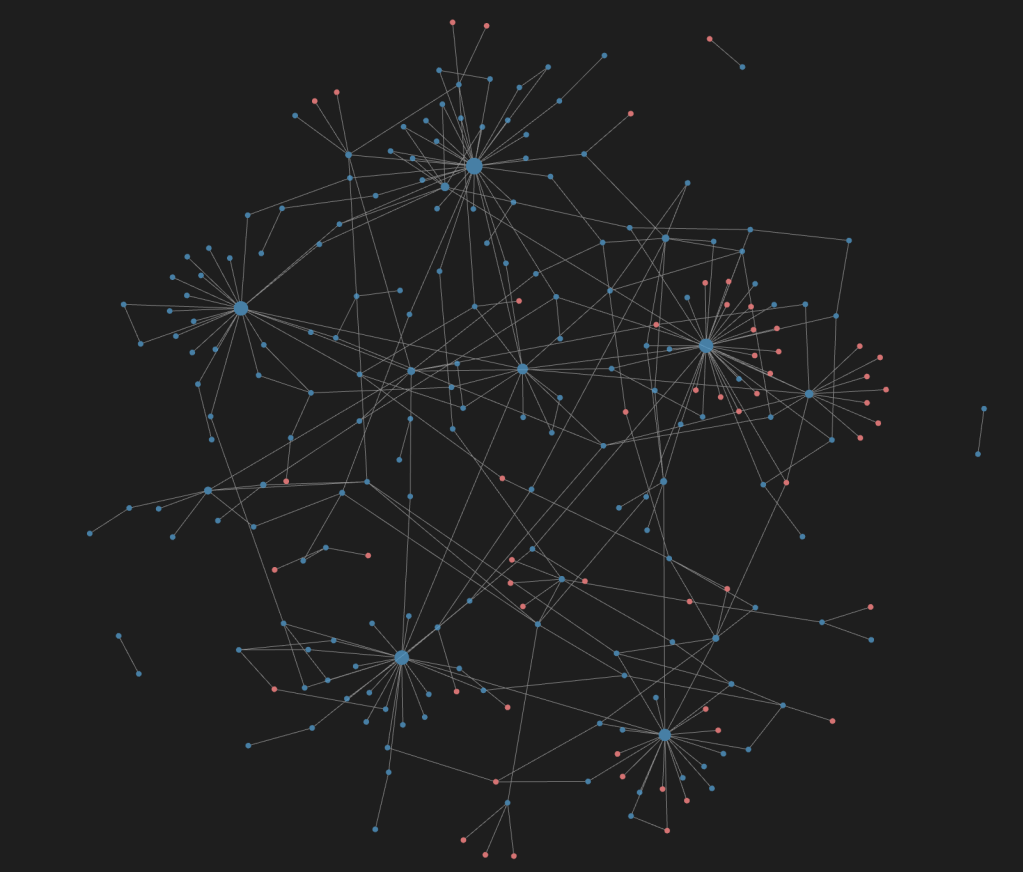

Map of a simple Zettelkasten in Obsidian (Example)

- The more notes that are connected to a note, the larger the circle icon on the map.

- Blue circles are notes with content written in them

- Red circles are concepts referenced, but there is no note created for them yet.

- You link notes in Obsidian by using the double brackets [[Note]] to reference others notes.